Before you can start a successful journey mapping initiative, it’s critical to think through the specific journey you want to map. Participants in our Best Practices in Journey Mapping survey referred to this as “Select the right journey to map.”

This takes deliberate thought. If you go too broad, you may not have enough detail to move the needed parts. If you go too narrow, the impact may be too small.

There are three types of maps to consider:

Let’s talk about each of these in turn, then discuss how to decide.

This is a common approach when you’re early in your customer experience journey. This map shows how customers go from awareness through purchasing with you, on through ongoing service and loyalty.

This approach is commonly used as a high-level diagnostic, to discover where problems exist in the journey. For example, when we worked with Be The Match, the National Marrow Donor Program, they wanted to understand where challenges occurred in their member journey. Similarly, when another B2B client wanted to understand how the largest housing companies build homes, so they could find areas to provide more value, this also required an end-to-end experience map.

Experience maps often use a buyer model as a framework. Your marketing department probably uses a buyer model, although there isn’t much consistency across organizations. I’m a fan of the Model of Consumer Behavior by Philip Kotler, which uses five phases:

This is a pretty typical framework, showing the initial trigger (Need Recognition), the pre-purchase process (Information Search and Evaluation of Alternatives), the actual purchase and then what happens after the purchase.

Regardless of what buyer model you use, this framework serves to organize your approach – we’ll come back to this later.

Think of the end-to-end experience map somewhat like a map of the United States. You would show a map of the country to somebody who’s new to the country, or somebody trying to get a handle on the lay of the land or plan a long trip. But it’s not going to help you get to downtown Cleveland.

Similarly, an experience map is really good at giving you an overview of how everything fits together, useful for planning an approach. But it’s not at a low enough fidelity to help you specifically solve the problems you discover. While they may not be as detailed as a specific journey map, experience maps are very useful at culture change, and showing what it’s like to work with you.

This doesn’t make experience maps either good or bad. Their usage just depends on your needs.

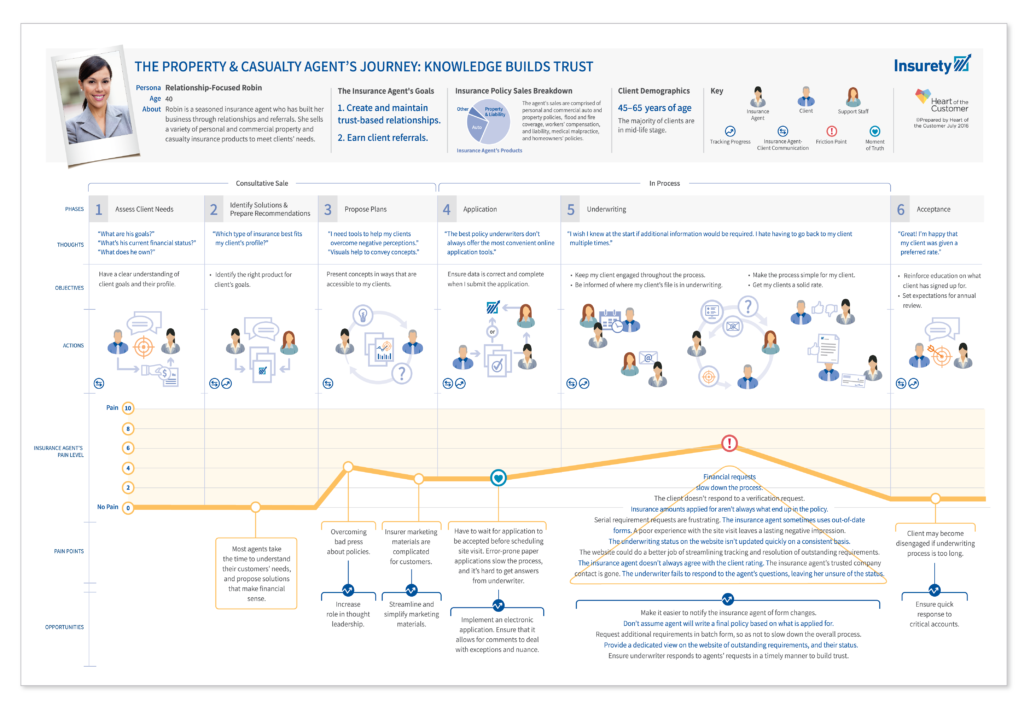

Next down is a map of a specific journey within the overall experience. Some examples from our previous work include studying the underwriting phase of a life insurance experience, the new member experience at the YMCA, or the radiology journey at Meridian Health.

We wrote about the YMCA mapping project in our recent article in Quirk’s market research magazine. They wanted to improve the retention of new members. This is a great example of a journey map – to study a specific piece of the overall experience to understand what friction may be impacting your customers.

The phases of a journey map will vary significantly based on the journey being studied. For the Y, we focused on three sub-journeys: visiting the Y to workout, taking a class, and attending a Wellness Consultation (a one-on-one time with a physical trainer offered to new members).

Of course, none of these phases would have made any sense when we studied the advanced radiology journey at Meridian Health (read the book Mapping Experiences for more detail). There we used five phases: Pre-Appointment, Drive & Arrive, Procedure, Follow-Up, and Outcome.

The benefits of a specific journey map are that it highlights the specific need, and it leads directly to action planning. The trade-off is that it offers limited help on the rest of the experience. For example, the YMCA’s mapping process certainly uncovered challenges that apply to every member. But most of the items were specific to new members. Longer-term members – as well as older members – likely experience different sources of friction.

Similarly, while some of Meridian’s findings may apply to other capabilities, much of what we discovered was specific to advanced radiology.

The most specific type of map is one that’s tied into a specific touch point, such as the web experience. Touch Point Maps are the most specific, and are very different from the first two, in that they don’t often involve cross-functional teams, and are not often used to change culture. These maps fit better user experience than customer experience.

To select the right type of map, you need to start with what you’re trying to accomplish. Then select the right level of fidelity for the change you need to create.